I met Nick1 on the California Zephyr train from Emeryville CA to Chicago IL. I had already met Peng, a Laotian life insurance agent from Richmond CA, and Adriana, a sophomore geology student at U of Chicago, when Nick boarded in Reno NV. Adriana had been keeping her eyes open for wild horses and we finally spotted a cluster shortly after departing the station. “Oh, yeah, the horses?” Nick said, pulling up a seat next to me in the lounge car. “They’re like raccoons around here. They keep trying to get rid of them, but they can’t seem to do it.”

“You’re from around here?” I ask.

“Yep, just got on in Reno. Headed for Baltimore.”

Though I’ve been traveling around the country primarily to visit my friends, most of my most interesting and meaningful experiences so far have been with strangers. One of the amazing things about travel—and train travel in particular—is meeting strangers and hearing their stories. I’ve been surprised and amazed at how easily I meet strangers and how quickly they open up their life stories to me once I started being open to it.

Something I’ve been thinking about recently is the importance of being able to converse with a variety of people who are different from me. Having grown up in a more-or-less homogenous environment of middle-class, liberal, college-educated, city-dwellers, there’s a lot of people who I never really learned how to interact with, how to converse with, and how to disagree with. It’s easy to dismiss this idea, to say, “Just interact with them like people,” but I’ve never found it to be that simple. There’s always cultural and political differences that create awkwardness and tension. In the past I’ve avoided interacting much with people whose lives vary significantly from my own, but I don’t think that is an ethical, productive, or compassionate way to orient oneself to the world. No longer.

A couple weeks earlier, I ran into an amazing coincidence while riding the Coast Starlight2 from Portland OR to Emeryville CA. It was evening and I was sitting alone at one of the lounge car tables, writing out postcards to friends. Behind me a group of three white kids—more or less my age, clearly new friends—were discussing the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, which had just passed. At the table across the aisle from them, an older black man turned to them and said, “Pardon me for interrupting, but I want to ask a question of you: who, besides Martin Luther King, do you think was the most significant figure in the civil rights movement?”

Towards the end of the ensuing conversation, the older black man began to tell his life story. He talked about how he admired Malcolm X. He said that during the civil rights movement he changed his name and took on an African last name: Emeka. He said that two of his children grew up to be college professors.

At this point I turned around to say, “I couldn’t help but overhear your conversation. Where do your children teach?”

“Well, one teaches at Oberlin College–”

“Oh my god. I took a class with your son.”

Back on the California Zephyr I was relating this story to another new friend. I wanted to share an example of how small the world is when you ride trains and of how many connections there must be that we never even discover. He was an older white man from the woods of Oregon, traveling with a woman who seemed to be his wife. When I finished my story he said, “You know, people have twisted what the civil rights movement meant these days. They’ve made it mean what they want it to mean and forgotten what it was really about.”

I nodded, despite a sinking feeling in my stomach. A statement as general as that, I can actually agree with. Towards the end of his life, MLK Jr. was preaching a politics of revolution—something more than just law reform. He was calling on his followers to question the fundamentals upon which American society rests. This, I believe, is a message that has gotten lost in the intervening years. And so I nodded in agreement, despite my dread for what this man was about to say. Behind him, I saw his wife roll her eyes and move to leave, returning back to their seats.

“No, I’m sorry, I’ve got to say my piece. I can’t keep quiet about this any longer. I mean, Martin Luther King was a preacher wasn’t he? The civil rights movement happened in the churches.”

A large part of learning to interact with people whose lives are different from my own is discovering how to handle points of conflict. I make no secret that my politics lean left, often radically. In fact I assigned myself the task of radicalizing myself this past year in Oberlin. I’m not so arrogant as to believe that my understanding of the world is objective and that the opinions I form are perfectly rational. I know that the environment I immerse myself in—the books and articles I read, the radio I listen to, the people I talk to—these shape my political beliefs in ways that are subconscious and beyond my understanding. Oberlin’s politics, which emphasize standing with those whose lives are being systematically shortened and whose autonomy is being circumscribed, appeal to me and I wanted to drench myself in them before entering the so-called real world. I wanted to build a buffer around my beliefs before subjecting myself to the culture of larger American society.

And now that I’m out in the world, meeting strangers, interacting with people whose beliefs differ from mine—who believe in gun rights, who believe in the sacredness of rape jokes, who think that the Obama administration is running the country into the ground, who say that someday I will find Jesus, and so on—I keep finding these points of conflict which are also small decision points: do I speak up or do I bite my tongue?

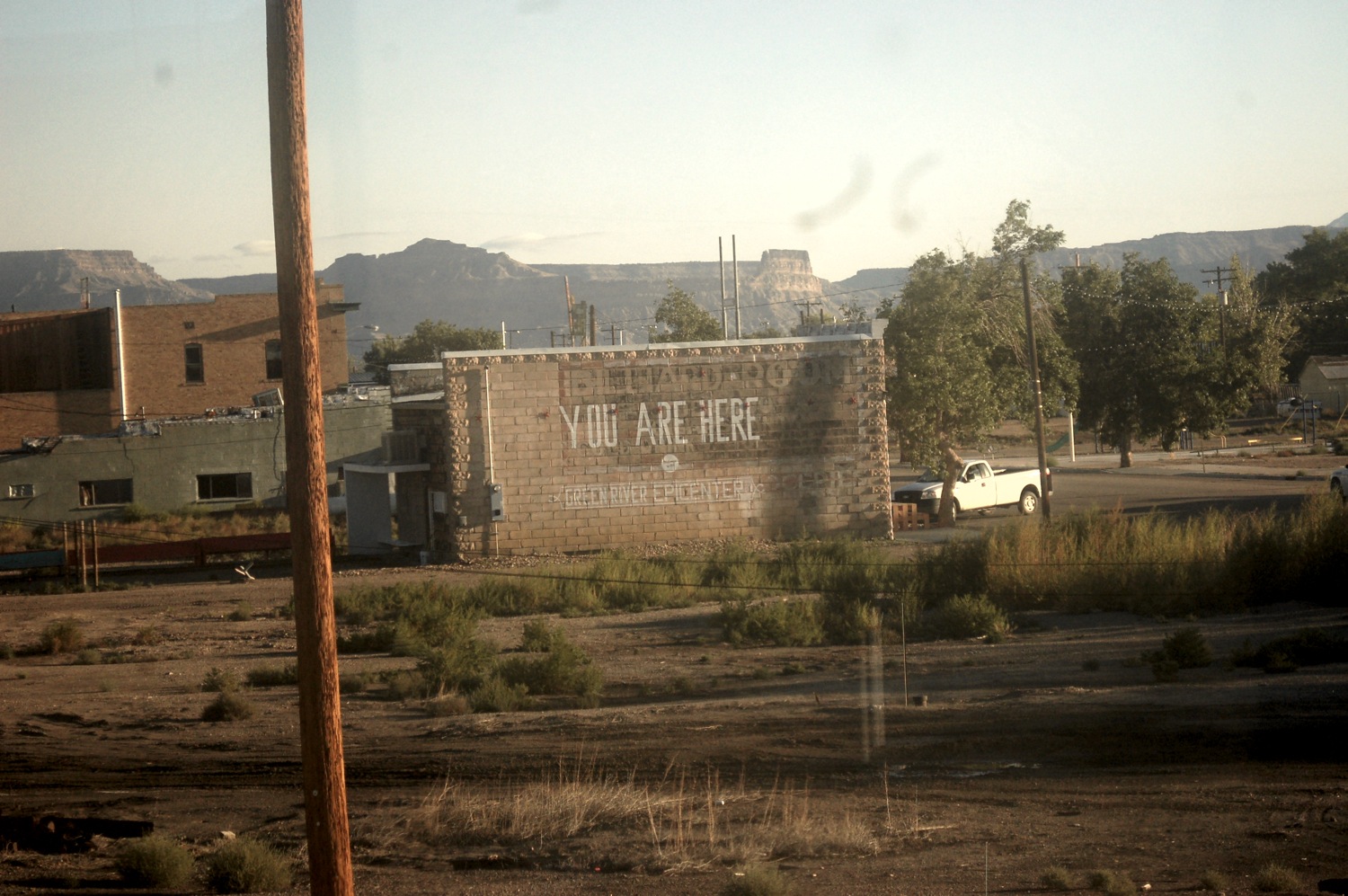

Later, Nick and my older friend—let’s call him Peter, a strong Christian name—had a conversation about searching the desert for metal relics.3 We were passing through Utah4 and they were talking about scouring the desert for old aluminum cans, railroad ties, and bullet casings. They talked about melting bullet casings down for metal or refilling them and selling them anew. They talked about gun rights. The phrase, “When you criminalize guns, only criminals will have guns,” was uttered. I bit my tongue.

“I mean,” said Peter, “there will always be criminals. Some people are just bad. Reform doesn’t work. You can see that because of how many end up right back in prison after they’re released.”

“Well,” I said, letting the filter slip, “that’s because prison isn’t designed to reform people. That’s not its purpose.”

“Now hold on,” Nick jumped in, “I think maybe you two are saying the same thing.”

But we weren’t.

I think part of my fascination with Nick as a character, out of the cast of characters I’ve met on the train, is that he was broken and that he knew it. The paradox of making friends on a train is that you can know them very intensely for a very short time. Your overlap in life is limited—bounded by your departure and arrival stations.

When Nick first boarded the train he told me he had brought a bottle of Southern Comfort on board to drink. “I’ve got years of experience as a functioning alcoholic,” he said, with no hint of irony. He told me and Peng that he was an animator and showed us a couple of his “less offensive” animations. They were the variety of nonsensical slightly off-putting flash animations my cohort and I used to love in middle school. When I broached a conversation about whether making rape jokes is okay he prefaced his defense of rape jokes with, “Listen, I don’t want to get into my whole family history, but let’s just say… I’ve been there.” He said, “Making rape jokes is my way of making people think about how fucked up it is.” I don’t agree, but I listened and I bit my tongue.

Nick told me that he’d lived in Baltimore for a year, but he’d been fucked up with severe depression and suicidal tendencies, so he’d moved back home to Reno for a while to get better. He was feeling better now and was on his way back out to Baltimore to give it another go.

Later, during our conversation with Peter, the topic turned to religion (as I was gathering it often did with Peter) and Nick abruptly stood up and held out his hand. “You know what? It’s been great talking to you, but I’m gonna go now. You had me until you started talking about religion.”

“It’s been great talking to you. No, just wait a second, hear me out. I was just like you at your age–”

“No, look, you don’t know me. I’ve been there. I’ve given religion a shot and you know what? Religion rejected me.”

“I was like you when I was your age. My father taught me–”

“See, that’s one difference between you and me. You had a father to teach you things. I never had a father. I never had a family.”

“All I’m saying is I realized somewhere along the way that we have to treat out fellow humans with compassion and that’s what Jesus taught me.”

“Yeah, but look at all those Christians who have done terrible things in the name of Christianity.”

“They weren’t Christians. They might say they were, but they weren’t Christians.”

“Look, all I’m saying is–”

“The founding fathers wanted to give us freedom of religion, not freedom from religion.”

I listened, and held my tongue.

Later, while we were hanging out with Peng, Adriana, Rafeel (a quiet Pakistani man, roughly my age, on vacation from his job in Seattle), Nick brought over a new friend. “Guys,” he said, “meet Carson.”

Carson is a 30-year old man from Durban, South Africa, but he has an even younger feel to him. As the six of us hung out and chatted in the lounge car, late into the night—three of us (myself included) getting drunk on Southern Comfort and Dr. Pepper, the other three remaining mostly sober—Carson related his life story to us.

Carson is ethnically ambiguous. He has dark skin and looks like he could easily be either Black or Indian South African, quite probably some combination of each. He said he grew up in a strict Hindi household in Durban, but never really took to it and never felt like Durban was home. When he was 21, he moved to the United States to find somewhere that felt like home and he’s been moving from place to place ever since, still looking.

He’s on the train now, he said, meeting someone in Boulder City. It’s unclear whether he meant Boulder City NV or Boulder CO and he didn’t seem to know himself, but either way he was far past his stop or on the wrong train or potentially both. When we pointed this out, he didn’t seem too concerned. He just made up his mind to follow to train to its terminus in Chicago.

When I cracked open a bottle of wine, the topic of wine tasting came up and Carson asked what Napa Valley is like. Would someone like him get along there? Nick tried to tell him how racist Napa Valley is, while Peng—a resident of the north bay herself—tried to insist that it isn’t racist so much as it is classist.

Around the third time that Nick felt to need to casually reassert that he and whoever he happened to be sitting next to are not gay, Peng said, “We know already!” I mentioned that queer politics are one of my major areas of interest and Nick looked surprised and then pensive. When the topic turned to gay marriage, I did my best to summarize my complicated feelings about marriage. Nick said, “You know what? The last few times I voted against gay marriage. And it’s not because I have anything against gays. I was trying to look out for you guys,” (I didn’t bother to correct him.) “I’ve been married. I know what it’s like. But next time, I’m just gonna vote for it, and y’all can figure it out for yourself.”

“You’ve been married?” Peng said, surprised.

Later, I thought about telling Carson that he’ll never find somewhere that feels like home until he can settle down in one place and build his own community—and maybe not even then and maybe that’s OK. Not everyone needs one place to call home. I thought about telling Nick to seek help for his drinking and his emotional traumas. But really, what could I do? It’s not my job to fix these short-term friends I make on the trains, get to know for a day and an evening, and then part ways with,—nor would I have the time, energy, or authority to do so if it were. All I can do is listen.

-

Actually, to be perfectly honest, my memory is such that I can’t remember if Nick is his name or a name that I’ve only just made up as a placeholder. ↩

-

Amtrak routes get such lovely romantic names: Coast Starlight, California Zephyr, Pacific Surfliner, &c. ↩

-

Sidenote: when Peter sat down with us, Nick felt the need to clarify that it was okay for him to join us because, “We’re not gay.” I resist the urge to chime in, “Speak for yourself, buddy!” ↩

-

The most gorgeous state I’ve traveled through, with its wide flat desert and strange lunar rock formations. ↩

Summeralities doesn’t have a commenting system, but I love getting feedback, thoughts, questions, and ideas. Please do send those to me! harris@chromamine.com. ♥

or previously: Does he look good from the front? in journal