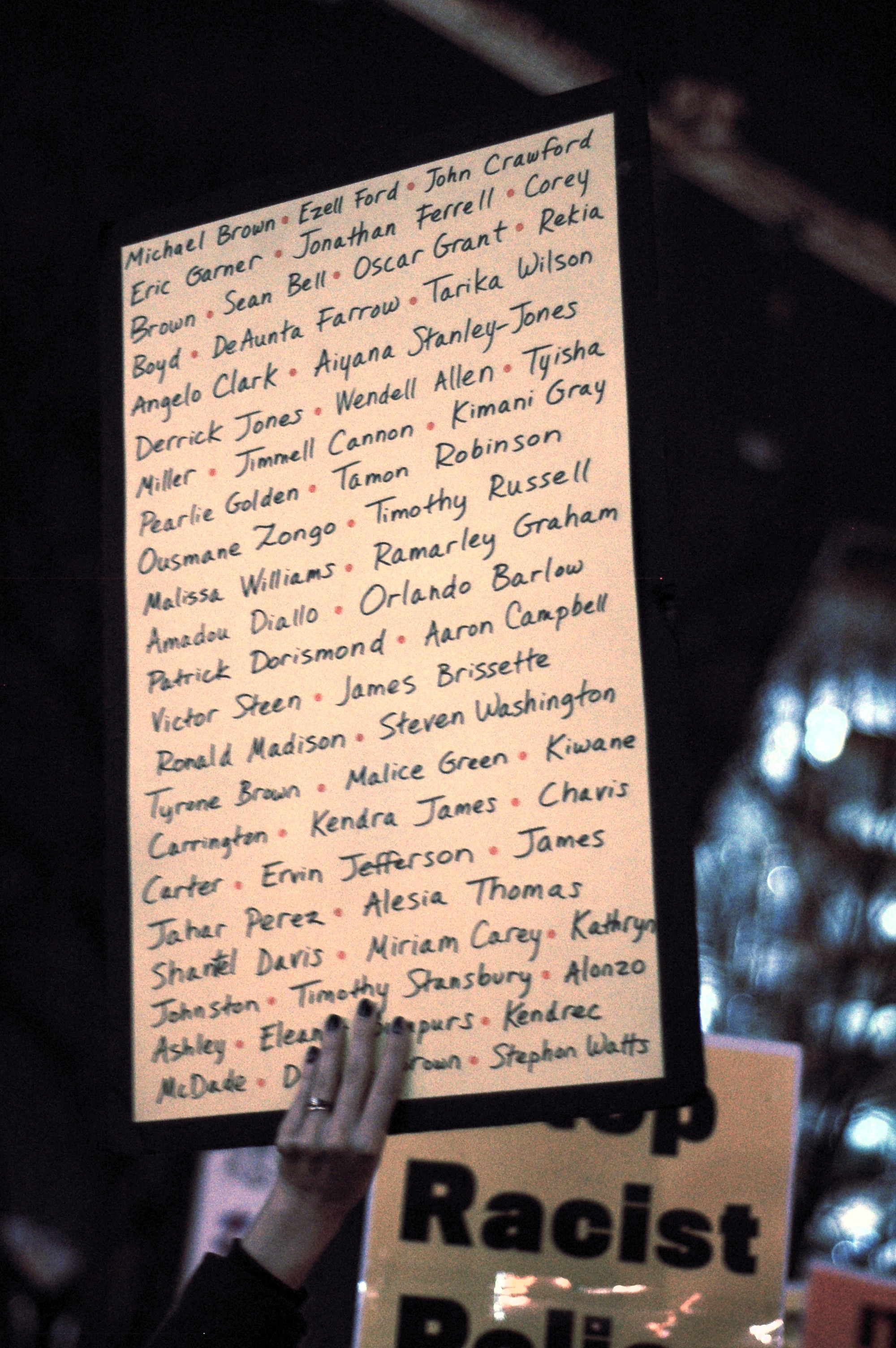

I don’t know what to say about the recent events in Ferguson MO and the failure to indict Darren Wilson for his murder of Michael Brown. I don’t want to argue with people who believe this isn’t a race issue or who believe that justice somehow has been sufficiently served. I’ve been spending a lot of time with the news and that’s exhausting enough. I don’t want to be silent because silence is complicity but neither do I believe I have an important perspective to add. I’m pretty good at collecting things that other people have said, so presented here are some scraps of writing that I find myself referring to lately and a few of my own thoughts.

Often, first, I find myself returning to poetry. It allows me to reflect while providing a respite from the continuous chaos and stress of news and analysis. I start sometimes with this poem:

Rehearsal

i saw

three little black boys

lying in a grave yard

i couldn’t tell

if they were playing

or practicing.— Baba Lukata

It breaks my heart every time I read it.

And then, sometimes, I read this one:

What Year Was Heaven Desegregated?

Watching the news about Diallo, my eight year-old cousin, Jake,

asks why don’t they build black people

with bulletproof skin? I tell Jake there’s another planet, where

humans change colors like mood rings.

You wake up Scottish, and fall asleep Chinese; enter a theatre

Persian, and exit Puerto Rican. And Earth

is a junkyard planet, where they send all the broken humans

who are stuck in one color. That pseudo-

angels in the world before this offer deals to black fetuses, to give up

their seats on the shuttle to earth, say: wait

for the next one, conditions will improve. Then Jake asks do they

have ghettos in the afterlife? Seven years ago

I sat in a car, an antenna filled with crack cocaine smoldering

between my lips, the smoke spreading

in my lungs, like the legs of Joseph Stalin’s mom in the delivery

room. An undercover piglet hoofed up

to the window. My buddy busted an illegal u-turn, screeched

the wrong way down a one-way street.

I chucked the antenna, shoved the crack rock up my asshole.

The cops swooped in from all sides,

yanked me out. I clutched my ass cheeks like a third fist gripping

a winning lotto ticket. The cop yelled,

White boys only come in this neighborhood for two reasons: to steal

cars and buy drugs. You already got wheels.

I ran into the burning building of my mind. I couldn’t see shit.

It was filled with crack smoke. I dug

through the ashes of my conscience, till I found my educated, white

male dialect, which I stuck in my voice box

and pushed play. Officer, I’m going to be honest with you: Blah,

blah, blah. See, the sad truth is my skin

said everything he needed to know. My skin whispered into his pink

ear, I’m white. You can’t pin shit on this

pale fabric. This pasty cloth is pin resistant. Now slap my wrist,

so I can go home, take this rock out

of my ass, and smoke it. If Diallo was white, the bullets would’ve

bounced off his chest like spitballs. But

his execution does prove that a black man with a wallet is as dangerous

to the cops as a black man with an Uzi.

Maybe he whipped that wallet out like a grenade, hollered, I buy,

therefore I am an American. Or maybe

he just said, hey man, my tax money paid for two of the bullets

in that gun. Last year on vacation in DC,

little Jake wondered how come there’s a Vietnam wall, Abe Lincoln’s

house, a Holocaust building, but nothing

about slavery? No thousand-foot sculpture of a whip. No

giant dollar bill dipped in blood.

Is it ‘cause there’s no Hitler to blame it on, no donkey to stick it on?

Are they afraid the blacks will want a settlement?

I mean, if Japanese-Americans locked up in internment camps

for five years cashed out at thirty g’s, what’s

the price tag on a three-hundred-year session with a dominatrix

who’s not pretending? And the white people

say we gave ‘em February. Black History Month. But it’s so much

easier to have a month than an actual

conversation. Jake, life is one big song, and we are the chorus.

Riding the subway is a chorus. Driving

the freeway is a chorus. But you gotta stay ready, ‘cause you never

know when the other instruments will

drop out, and ta-dah—it’s your moment in the lit spot, the barometer

of your humanity, and you’ll hear the footsteps

of a hush, rushing through the theater, as you aim for the high notes

with the bow and arrow in your throat.— Jeffrey McDaniel

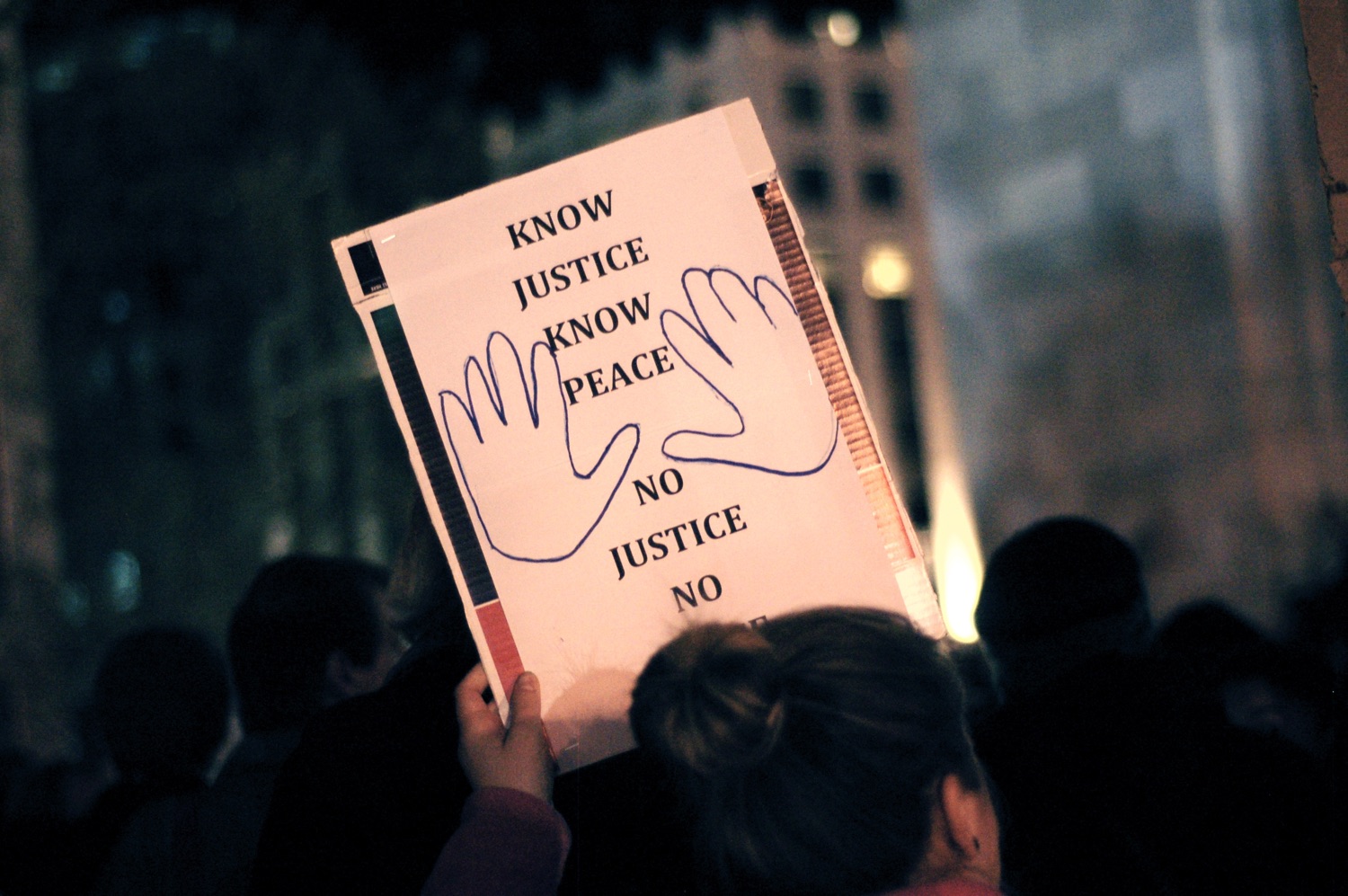

Amid calls for peace from Darren Wilson’s defenders as well as putative allies of activists (e.g., Obama), I find myself thinking a lot about peace, non-violence, and violence. I’ve seen the word “violent” in the news used to describe everything from personal physical injury to looting to blocking streets as though those are all the same crime and should be treated with equal condemnation. They are not and should not. And though I don’t condone violence, I know that “Peace!” is the rallying cry of the status quo. I can’t concede that passively accepting a violent state is more ethical than disruptive and violent resistance nor do I think it is my place to tell black people how they should react to their continued oppression.

This excellent Martin Luther King quote has been passed around a bunch lately:

I would be the first to say that I am still committed to militant, powerful, massive, non-violence as the most potent weapon in grappling with the problem from a direct action point of view… But it is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society. These conditions are the things that cause individuals to feel that they have no other alternative than to engage in violent rebellions to get attention. And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard.

I’ve also been thinking about this one from James Baldwin, talking about the militancy of Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam during the civil rights era:

I, in any case, certainly refuse to be put in the position of denying the truth of Malcolm’s statements simply because I disagree with his conclusions, or in order to pacify the liberal conscience. Things are as bad as the Muslims say they are—in fact, they are worse, and the Muslims do not help matters—but there is no reason that black men should be expected to be more patient, more forebearing, more farseeing than whites; indeed quite the contrary. The real reason that non-violence is considered to be a virtue in Negroes—I am not speaking now of its racial value, another matter altogether—is that white men do not want their lives, their self-image, or their property threatened.

And this one from Arundhati Roy:

What does peace mean to the poor who are being actively robbed of their resources and for whom everyday life is a grim battle for water, shelter, survival and, above all, some semblance of dignity? For them, peace is war. We know very well who benefits from war in the age of Empire. But we must also ask ourselves honestly who benefits from peace in the age of Empire? War mongering is criminal. But talking of peace without talking of justice could easily become advocacy for a kind of capitulation. And talking of justice without unmasking the institutions and the systems that perpetrate injustice, is beyond hypocritical.

Even white President John F. Kennedy famously said:

Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.

And the other day, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote a wonderful piece:

What clearly cannot be said is that violence and nonviolence are tools, and that violence—like nonviolence—sometimes works. “Property damage and looting impede social progress,” Jonathan Chait wrote Tuesday. He delivered this sentence with unearned authority. Taken together, Property damage and looting have been the most effective tools of social progress for white people in America. It describes everything from enslavement to Jim Crow laws to lynching to red-lining.

“Property damage and looting”—perhaps more than nonviolence—has also been a significant tool in black “social progress.” In 1851, when Shadrach Minkins was snatched off the streets of Boston under the authority of the Fugitive Slave Law, abolitionists “stormed the courtroom” and “overpowered the federal guards” to set Minkins free. That same year, when slaveholders came to Christiana, Pennsylvania, to reclaim their property under the same law, they were not greeted with prayer and hymnals but with gunfire.

“Property damage and looting” is a fairly accurate description of the emancipation of black people in 1865, who only five years earlier constituted some $4 billion in property. The Civil Rights Bill of 1964 is inseparable from the threat of riots. The housing bill of 1968—the most proactive civil-rights legislation on the books—is a direct response to the riots that swept American cities after King was killed. Violence, lingering on the outside, often backed nonviolence during the civil-rights movement.

One night in high school, or maybe it was one of my early summers back home from college, I was sitting in a car with a few of my white friends. It was after dark and the public park we were stopped in was legally closed. A cop car pulled up alongside us. I was stoned, as people sometimes are, and terrified. We knew the park closed at sundown, but we played dumb. “Oh, sorry, officer, we didn’t realize it was closed. We must have missed that sign at the gate.” Maybe we smelled of weed. Maybe the cop didn’t notice. He let us go and we drove off, out of the park, back to the safety of someone’s home.

We were a group of young, stupid, mostly white kids and one ethnically ambiguous kid. Years later, reading Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow for the first time, it occurred to me that, if we had been a group of black kids instead, that interaction would have gone very differently.

If you’ve never read The New Jim Crow, and you don’t understand how racism pervades our criminal justice system and touches all our lives, you must read it. It changed the way I see the world. And when you finish Alexander, go back and read Baldwin. Go return to MLK’s speeches and find the revolutionary parts that were misinterpreted, toned down, or omitted for you in elementary school.

I am not white, but I am nevertheless the beneficiary of racial privilege many times over. I hate it. My soul rebels against it. I don’t know what else there is left for me to say.

Further Reading

Not much else, but, like many of you, I’ve been reading a lot over the past few days. Here’s a few collected links of things that I’ve personally found insightful, reassuring, elucidating, or important:

-

Barack Obama, Ferguson, and the Evidence of Things Unsaid, Ta-Nehisi Coates

Black people know what cannot be said. What clearly cannot be said is that the events of Ferguson do not begin with Michael Brown lying dead in the street, but with policies set forth by government at every level. What clearly cannot be said is that the people of Ferguson are regularly plundered, as their grandparents were plundered, and generally regarded as a slush-fund for the government that has pledged to protect them.

-

How Not To Use A Grand Jury, Jeffrey Toobin

But the goal of criminal law is to be fair—to treat similarly situated people similarly—as well as to reach just results. McCulloch gave Wilson’s case special treatment. He turned it over to the grand jury, a rarity itself, and then used the investigation as a document dump, an approach that is virtually without precedent in the law of Missouri or anywhere else. Buried underneath every scrap of evidence McCulloch could find, the grand jury threw up its hands and said that a crime could not be proved.

-

Today in Tabs: I Will Only Bleed Here, Bijan Stephen

I am a writer. I believe words have power. Or, maybe it’s this: That I must believe words have power because this is the only thing I can do, this is the only thing I have, and I need it to be enough.

-

Telling My Son About Ferguson, Michelle Alexander

I begin telling him the truth and his face contorts. The glowing innocence is wiped away as his eyes flash first with fear, then anger. “No!,” he erupts. “There has to be a trial! If you kill an unarmed man, don’t you at least have a trial?”

Summeralities doesn’t have a commenting system, but I love getting feedback, thoughts, questions, and ideas. Please do send those to me! harris@chromamine.com. ♥

or previously: Reasons to Write in journal